Prototyping with Artists at the Center

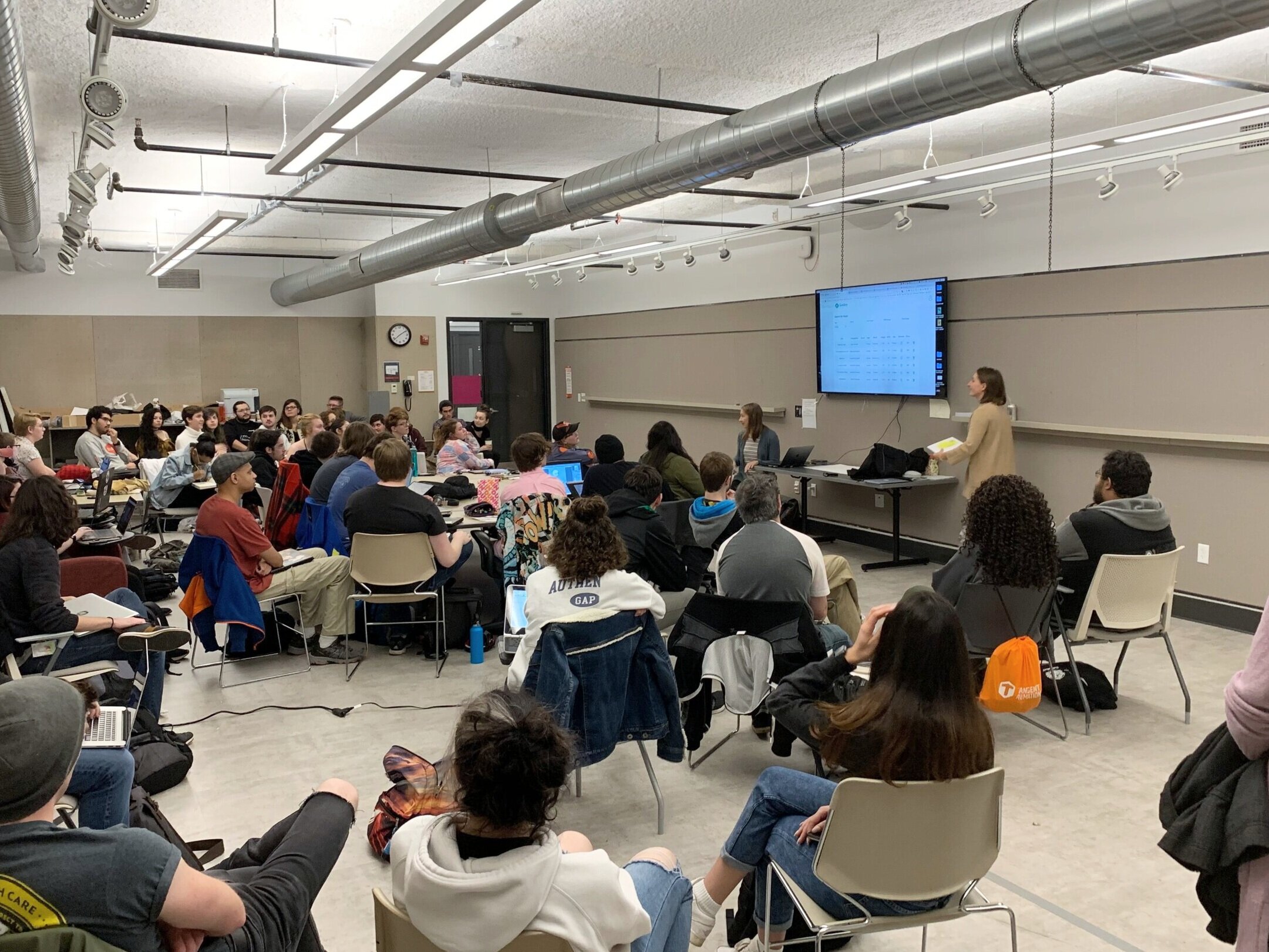

Lesley University film and animation seniors share feedback on the prototype platform. (photo credit: George Howard)

Last week, I visited Lesley University with Berklee/Open Music’s George Howard and Berklee graduate fellow and Open Music programmer Meghan Gaudet, and met with 60+ film and animation students to hear their thoughts on a prototype we’ve been building.

I asked, “Raise your hand if you would pay $10 for music for your films. Keep them raised if you’d pay $20. $30? $40?. . . $150?” The last hand went down.

What is the value of music? How much is a song worth? And how do artists decide how to price and describe their work?

Over the last few months, Berklee and MIT Connection Science have been developing a “decentralized and authoritative repository” for Berklee students to license their musical works to other student creators, such as filmmakers or animators. We believe that this prototype is a first step in implementing the interoperable vision of Open Music. We’ll unveil the prototype at the upcoming November 13 meeting - read on for a preview.

At the February 2019 Open Music meeting in Los Angeles, George Howard and MIT Connection Science/Open Music’s Thomas Hardjono and Eric Scace took advantage of the plentiful white board space and sketched out the beginnings of this concept. Combining their collective experience from the music industry and open source projects, they mapped out a foundation for emerging artists to upload, price and describe songs on their own terms, and make them licensable by trusted consumers - for starters: film, animation and video game design students.

Since then, with leadership from Alex “Sandy” Pentland, Toshiba Professor of Media, Arts and Sciences and Director of MIT Connection Science, a grassroots collective has worked with Thomas, Eric, George and myself to make it a reality. The team includes teenage producer/engineer Chris Kulis; open-source tech veterans like Irving Wladawsky-Berger, Mizan Chowdury, Induprakas Keri, Chandler Vaughn, Stephen Moore and Justin Anderson; Berklee and MIT grad student fellows Meghan Gaudet and Lucas Novak; plus Berklee student artists like Edward Sweeney and Emily Chiang.

So, why is this a big deal? Well, for starters, we’re working with Berklee musicians, the same ones who, in a few years, will join the ranks of Berklee alumni like Captain Marvel film scorer Pinar Toprak, Game of Thrones composer Ramin Djawadi and singer-songwriter Charlie Puth.

This is good, cool music.

Then, consider that we’re building a platform that no one owns, where the metadata and the songs themselves are tracked and stored in a decentralized manner on a blockchain, using metadata architecture that is compliant with DDEX standards. While Berklee and MIT are building the technology, it’s open source by design, held and controlled by no singular entity.

The data is portable. Artists own their data. It's good data, and they can take it with them.

Thanks to Sandy Pentland’s team of MIT data scientists, the same ones who advise nations and major companies on digital identity and attribution, we are using future proof solutions. A creator’s identity and attribution will be persistent after they leave Berklee and go onto successful careers, and will be compatible with other commonly used industry identifiers, such as ISNIs.

Creators have sovereignty over their identity and attribution, and thus over their careers.

We’ve started small, with, in the words of MIT’s Seymour Papert and Mitch Resnick, “low floors, wide walls and high ceilings”. We’re first working with controlled compositions: those with a single copyright holder for the composition and the recording. And, we’ve built a MongoDB backend with a metadata structure that will grow and adapt as we introduce more use cases. The platform is simple to deploy, and horizontally scalable. We are using microservices to implement technologies like smart contracts via Blockchain, file management and transaction processing (for more details, read the white paper here). It is extensible to new services, known, and unknown. The sky's the limit.

It works, using distributed, scalable technology that exists today.

One film student told us she wanted to use the search tag “feudal Japan”, as a few other students nodded their head in agreement. We cannot pretend to know how filmmakers want to search for music. We do know there’s a gap between how people search for music and how musicians describe their work. Our platform will facilitate these exact learnings, showing creators the crowdsourced results of how consumers actually search for music, and empowering them to learn from the market, while facilitating search and discovery for music consumers in their own language.

We've opened a feedback loop between consumers and creators.

At our core, we are teachers. This platform has been built by teachers, teachers who know a ton about tech and music, building with art students at the center. As industry metadata practices are on the verge of a huge change with the incoming MLC, and as change remains the one constant, we’re committed to educating artists about good data practices. And we’re building a platform that is as easy as building a website on Squarespace or doing your taxes on TurboTax. Might we even integrate required 30-second videos that teach about basic music copyright law? Hell yes.

We believe, deeply, in the power of education.

After we demo at our New York meeting in November, we want to work with you, Open Music members, and build together on top of this foundation. When it’s so easy for creators and consumers to exchange good, cool music, what diversity and abundance might this next generation create?